by Dan Lyons

Tesla CEO Elon Musk has done something amazing. In 2008, he took over an electric car company that was in danger of going out of business, and he’s turned it into one of the hottest companies in the world.

Tesla’s stock has tripled in the past six months. Its sexy Model S sedan is selling as fast as Tesla can make them, and the company has even posted a modest profit.

But more interesting than Tesla is Musk himself. He’s 41 years old, grew up in South Africa, and made a fortune as a co-founder of PayPal. In addition to running Tesla, he’s CEO of Space Exploration Technologies (aka SpaceX), which makes rockets and spacecraft and has won contracts from NASA.

But most important, Musk is a brilliant marketer, both of himself and his products. He’s so good, in fact, that lately people have started comparing him to another marketing genius -- Apple’s late CEO, Steve Jobs.

Like Jobs, Musk can be strong-willed, obnoxious, arrogant, and sarcastic. And, as with Jobs, a lot of what Musk does runs completely counter to conventional wisdom about marketing -- and yet, it works.

I would argue that right now Musk is the best marketer in Silicon Valley. I’d even argue that Tesla’s $12 billion market value (up from $3 billion a year ago) owes as much to Musk’s marketing skills as to anything related to revenues, earnings, or any other financial fundamentals.

How He Does It

Here are some of the ways Musk bucks convention and still manages to win:

He picks fights with journalists.

PR 101 says that when a story doesn’t go your way, you try to keep things quiet and deal with the editor, and maybe try to get a correction -- things like that. What you don’t do is go nuts and draw even more attention to an unflattering story.

Yet when the BBC show Top Gear ran a review of the Tesla Roadster that Musk didn’t like, Musk made a huge stink over a show most people (in America anyway) had never even heard of. Musk sued the BBC for libel. He lost in court, but won in the court of public opinion. The fight raised awareness of Tesla.

(Full disclosure: Back in 2008 I too became the subject of Musk’s ire because of an article I wrote in Newsweek that said Tesla was "losing its juice." No lawsuit, just an angry note to the editor. And now, five years later, lots of egg on my face.)

In February of this year, when a writer for the New York Times penned a negative piece about Tesla and claimed the battery in his Model S test car had died on a long drive, Musk went ballistic on Twitter, accusing the writer of fabricating his results. “NYTimes article about range in cold is fake,” he tweeted, following up with a blog post in which he wrote, “When the facts didn’t suit his opinion, he simply changed the facts.”

Steve Jobs also had a love-hate relationship with the press. In 2008, he started off an interview with New York Times columnist Joe Nocera by calling him “a slime bucket who gets most of his facts wrong.” Not what they teach you in PR school. And yet, I would argue more people came away from that exchange siding with Jobs than with Nocera.

How do Musk and Jobs pull this off? My theory is that most people hate journalists, so when a CEO bashes one of them, the world roots for the CEO. Plus, when Musk attacks his critics, he looks like a proud papa defending his kid. People admire him for sticking up for his product.

He taunts Wall Street.

Conventional wisdom is that CEOs should not rock the boat when it comes to investors. If the market’s running against you, you grin and bear it. Not Musk. For a long time, Tesla’s stock has been haunted by short-sellers -- people who have bet the stock will go down, and sometimes bash the company to help that process along. Last year, asked on Fox Business about the huge short interest in Tesla shares, Musk declared "there’s a tsunami of hurt coming for the shorts." Recently, when Tesla shares began rising, Musk took to Twitter to taunt the short-sellers who were getting crushed, writing, "Seems to be some stormy weather over in Shortville these days."

He likes to drop hints and build suspense.

Jobs was a master of suspense who would dodge questions about future products but do so in a way that only fueled more speculation. He knew that people love a mystery.

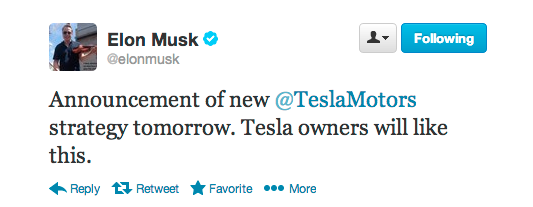

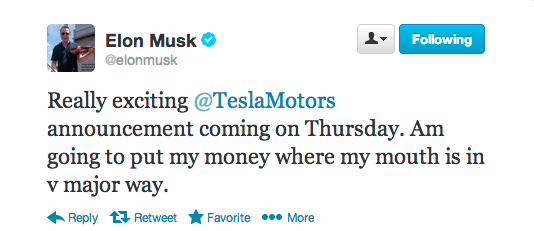

Musk does the same -- only he does it on Twitter. And every time he does this, the tech press jumps to write up the news that Musk just tweeted a hint about a new product. Then when the product is announced, the press all covers that, too. So Tesla gets loads of press for what otherwise might just be a press release that nobody would even write about.

“Announcement of new @TeslaMotors strategy tomorrow. Tesla owners will like this,” Musk tweeted on April 25, setting off a mini-frenzy of speculation about what Tesla might announce.

He gloats about his victories.

Sure, every CEO likes to announce good news. But Musk likes to go a little further and really rub it in. In the May 22nd press release announcing that Tesla had paid off its government loans ahead of schedule, Tesla also mentioned that “Following this payment, Tesla will be the only American car company to have repaid the government.” Tesla also pointed out that the money it got was not the same as the money spent to bail out big car makers. Tesla’s money came from the Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing Loan Program, which “is often confused with the financial bailouts provided to the then bankrupt GM and Chrysler, who were ineligible for the ATVM program, because a requirement of that program was good financial health.”

He thinks big and isn’t afraid to speak his mind.

Conventional wisdom says a CEO should stay “on message” and talk about whatever product(s) the company wants to tout right now. At the recent D11 conference, where Apple CEO Tim Cook was criticized for doing just that -- he ducked questions and was too bland -- Musk wowed the crowd by talking about putting people on Mars and a high-speed transportation system called a Hyperloop that could zip people from LA to San Francisco in half an hour. Sure, he also pulled the conversation back to Tesla. But now Tesla and its electric cars were set in the context of a space-age future -- great brand positioning.

He turns customers into evangelists.

One thing you learn very quickly as a tech journalist is that if you ever say anything even remotely negative about Apple, you will be attacked by legions of fanboys rushing out to tell the world that you’re stupid, or dishonest, or both. That’s because, over its 37-year history, Apple has built an army of fanatics who love the brand and everything it represents, so much so that they will stand in line for days in advance of a new iPhone release just so they can be first to get Apple’s new toy. (And also, I would argue, because they want the world to see them standing in line outside an Apple store. Now that is brand power.)

Tesla has started to become the same thing. Its customers don’t just like their cars; theylove their cars, and they love Tesla, and they want everyone in the world to feel the same way. When that negative story ran in the New York Times in February and Musk took to Twitter and his blog to complain, he unleashed an army of Tesla lovers who swarmed theTimes website and every other blog or website that ran an article about the kerfuffle. One group of Tesla owners actually spent the weekend driving the same route that the Timesjournalist had driven, in an attempt to discredit his story by proving that their cars didn’t run out of juice on the same trip.

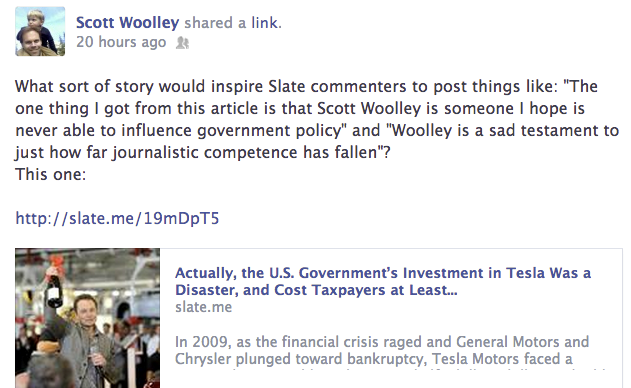

More recently, when my friend and former colleague Scott Woolley penned a piece for Slatearguing that the government got a poor return on its investment in Tesla, he was taken aback by the vitriolic comments that came swarming in.

The lesson? Tesla is a beloved brand with incredibly zealous fans. Those fans include loads of people who love Tesla even though they haven’t even bought a Tesla, and probably can’t afford one. (The Model S starts at $70,000 and can go over $100,000.)

Can you imagine having an army of people who love your company so much that, even though they can't afford your product, still feel the urge to defend you against critics?

Now that is what I call good marketing.

No comments:

Post a Comment